A Brief History of the Scottish Coinage

Synopsis

A brief history and outline of the development of a Scottish coinage system, including units, merks, ryals, bawbees, and more.

Climate Equals Coins

If you look at the timeline and development of different countries or empires and at which point a coinage was introduced in each of them, there has to be the correct socio-economic climate in place first. Looking onwards from the Roman and Greek Empires as to when other nations started adopting a coinage system; the natural order of basic settlements of people need to join and connect to create this climate. Once this starts to happen, urban areas develop and then become governed and centralised via a system of rule. These events normally dictate as and when coins appear and begin to be used as a means of trade.

Landlocked Countries and the Roman Effect

The second aspect of when and why countries started to produce their own coinage system and how that develops is the effect of surrounding countries upon them. Because we live in relatively secure times we forget how quickly and easily one ruler could decide to invade an adjacent country and the borders of countries could change. Scotland, like England has an advantage of not being totally landlocked, a reason why England was never successfully invaded after 1066.

In the same way that Roman coins were used in England after their invasion and then later crudely imitated by its inhabitants until they mastered the skill of hammering themselves, Celtic coins have been found north of the border and in many Roman areas of occupation; the most common being between the Hadrianic and Antonine fortification systems. This provides evidence of coins existing within the country, but equating this to a uniformed coinage system being present is a very different matter entirely.

Urban Development

Scotland and the origins of its coinage provide almost a perfect example of why no matter what the outside influence, the conditions within the country have to be correct for the need to adopt a system of coinage. If this were not true then it would be hard to explain why it took over a thousand years for a true Scottish coinage system to emerge after the existence of one in England. Scotland had not and did not quickly become an area of large urban settlements like many city dwellings in England did. Because of this, and as briefly outlined at the beginning of this piece, there wasn't the need for a coinage system. Each isolated Scottish town or village or settlement of people could and would have devised their own way of trading amongst themselves, and because there was not a transport system linking them together this didn't need to be the same in every area.

A Viking Mint on Scottish Soil?

Saying this however, the research and archaeological work done on this issue has provided certain clues as to where and when mints and coins were first minted north of the border. Although this evidence need not be examined in detail here, certain points such as the 9th century Stycas finds do tantalisingly point to their being a middle ages mint on Scottish soil, alas there is not enough evidence to prove this. It is also worth mentioning that when the Norsemen were in control of the Western and Northern Isles that coins minted close by have been recovered and that some of these found there way onto the mainland. Of course these were mostly English silver coins but amongst these were coins that show signs of a trade link between Scotland, Christian Europe, and the Moslem East. Further to this, local tradition north of the border relays the story that the Vikings were the first people to exploit the silver mines of Islay, even though there is no evidence of a Viking mint. While all this is food for thought when telling the story of the Scottish coinage, it can be no more than a footnote because of the lack of evidence in each case.

Anglo-Saxon Exodus and Patriotic Fervour

What we can be sure of however is the timeline of events through the Middle Ages and medieval times that assisted the initial formation of coins being minted on Scottish soil. The knock on effect of the Norman Conquest slowly brought the skills and methods needed for this to the people north of the border, both by the natural spread of knowledge and by the exodus of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy who fled to Scotland. With them, the English aristocracy brought the ideas for a central administration that became quite sophisticated very quickly, and brought about the need and the means to set up mints for hammering a national coinage.

In a similar way to how the Romans settled on English shores after their invasion and brought their revolutionary ideas, methods and skills with them, the English aristocracy did this for the Scots as when any learned group of people flee or settle their homeland. Whether this fact would every be acknowledged by the patriotic Scots in re-telling their history is probably very doubtful; though this is not to single out one nation. Many countries chose to edit their history to make it more favourable, though this naturally happened with the re-telling of stories over time before the advent of the printed word came about. The seemingly less heroic parts get left out in favour of the more patriotic parts that cause nationalistic pride. The English self deception over their historical continental invaders and their impact in favour of such iconic images as St. George slaying the dragon being just one example of this.

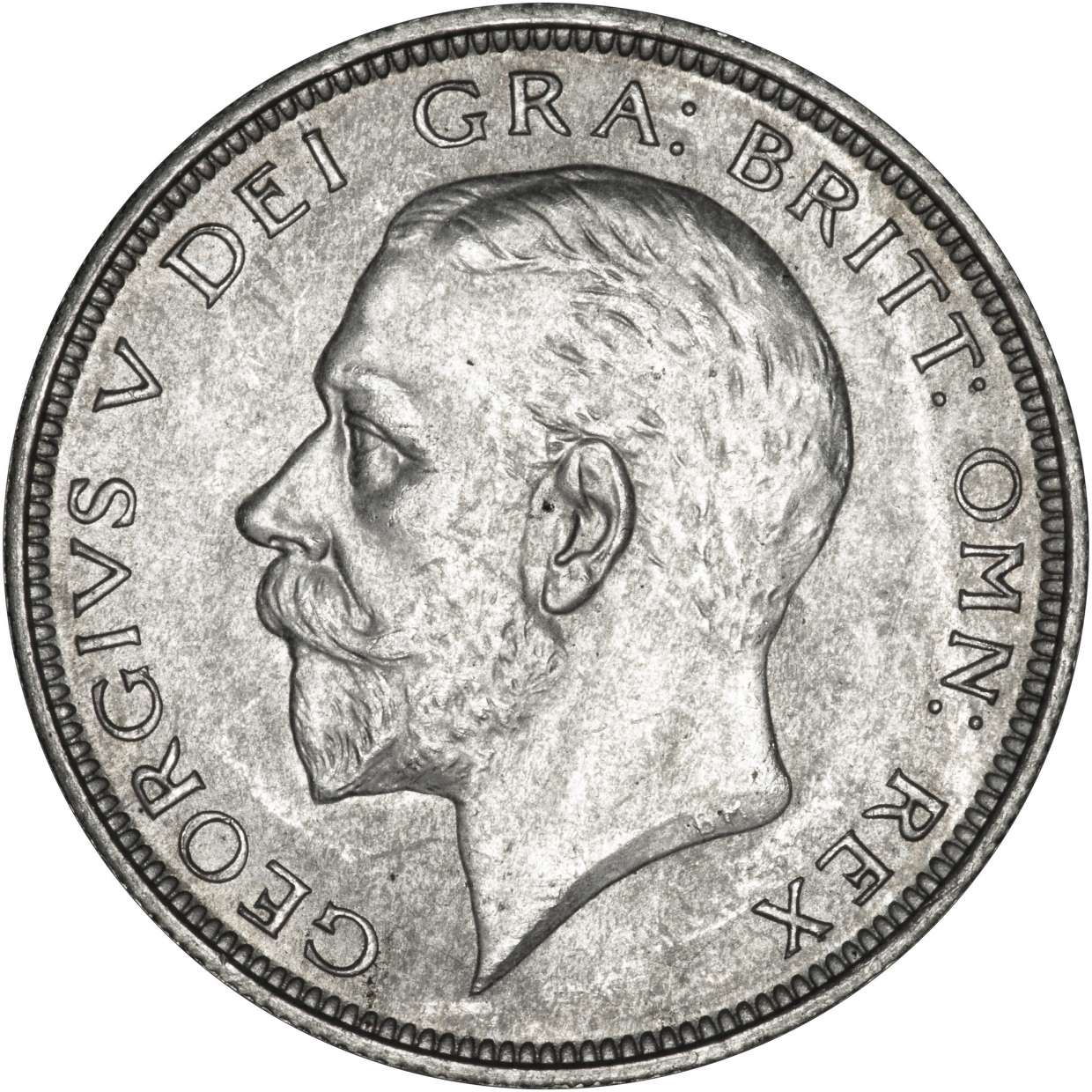

England and Scotland Alike?

For about two hundred years after the Anglo-Saxon settlers, the English and Scottish coins followed a very similar path and pattern. An examination of the various issues show very similar designs between the two and indeed a similar quality of silver and production. This facilitated easy trade between the two kingdoms. However, under the reign of James III (1460-1488) Scottish currency began to be reduced, debased and inflated relative to English currency. This trend continued during subsequent reigns, so that by the time the Pound Scots was abolished following the 1707 Act of Union, it took 12-13 Scottish Pence to equal one English Penny, with an official exchange rate of £12Scots=£1Sterling to facilitate an easier transition under the duodecimal/vigidecimal (12 and 20 base unit*) systems used by both England and Scotland.

Scottish Gold Lions and Portraits

The Gold coinage produced at the end of the 14th Century by the growing number of Scottish mints was a response to the large quantity of Gold coinage now being stocked and produced by the rest of Europe. The resulting 'Gold Lion' and 'Demi Lion' are distinctively Scottish coins in origin and appearance, unlike the mirroring silver coinages and are worth noting by themselves for this fact.

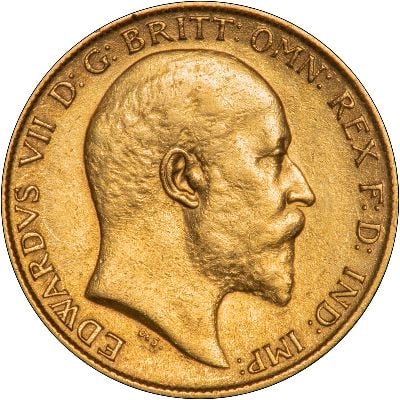

It is also probably worth mentioning the development of the portraits on the Scottish and English coinage. Up until the reign of Henry VII, the English monarch was always depicted on coins by a generic image of the king that was the same more of less no matter who sat on the throne. With the Scottish coinage following that of the English quite closely, this was also true for the coins of the Scots. What is interesting to know is that during the reign of James III in Scotland from 1460-88, two real attempts at portraiture were made for the silver groat issues, both of which pre-date the earliest English attempts on the silver shilling or testoon of Henry VII. These advances would lead to a great variety of portraits for certain monarchs such as James VI (who would later become James I of England) and demonstrate how far the Scottish Coinage had come since its inception.

1707 Union and the Close of the Edinburgh Mint

The eventual official union of England and Scotland in 1707 would finally lead to the closing of the Edinburgh mint. It would be interesting to ponder what would have become of the Scottish Coinage were it not for Union. In the upcoming ages of the early milled coin, whether the Scots would have continued to mirror the coinage of their closest neighbour is something we will never know. The tale of the formulation and development of the coinage deserves its own story, even if it is simply because it didn't have a coinage of its own for so long while its closest neighbour did. Through this, Scotland provides a perfect example of exactly why and when a country develops enough to require a coinage system of its own, something most people take for granted in their everyday lives but probably without ever asking why it came about, when it came about and what it was put in place for.

*Under which 12 Pennies equalled a shilling, and 20 shillings equalled a pound. This system may seem ludicrously complicated to people used to decimalised currencies, but it made sense back when a semi-numerate population could more easily divide the denominations into fractions, including thirds and quarters, as well as halves, and when few would have been dealing with sums of more than a few shillings in most transactions.

You may be intersted in The Coin, a Poem by Edwin Morgan

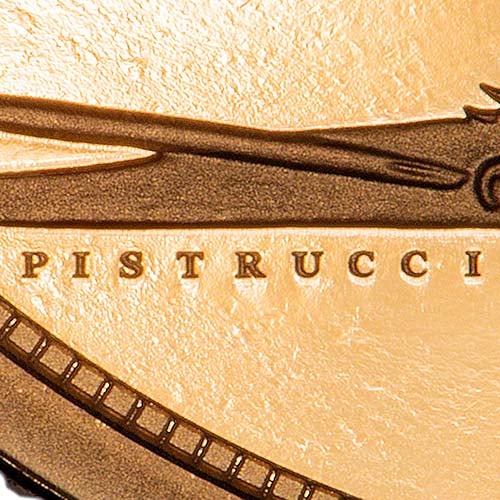

The Story of the Gold Sovereign - If you are interested in the history of the British gold sovereign, you can view our Gold Sovereign Guide.

If you want to find the value of a coin you own, please take a look at our page I've Found An Old Coin, What's It Worth?

Related Blog Articles

This guide and its content is copyright of Chard (1964) Ltd - © Chard (1964) Ltd 2024. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited.

We are not financial advisers and we would always recommend that you consult with one prior to making any investment decision.

You can read more about copyright or our advice disclaimer on these links.